Te Tiriti Explained Further

Te Tiriti Explained Further

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, New Zealand\'s founding document signed in 1840, continues to be a source of debate and misunderstanding.

As reported by RNZ, recent surveys reveal significant knowledge gaps among both Māori and non-Māori regarding the Treaty\'s content and implications, highlighting the need for ongoing education and dialogue about this crucial agreement.

The knowledge gaps around the Treaty of Waitangi\'s content and implications, are a reminder of how essential ongoing education and dialogue are for fostering understanding and respect for this foundational document.

The Treaty plays a central role in shaping New Zealand\'s history and its contemporary society, so ensuring that both Māori and non-Māori communities are informed is crucial for building strong, equitable relationships.

The Doctrine of Discovery Debate

The Doctrine of Discovery, a 15th-century legal framework that justified European colonization of Indigenous lands, has been a subject of intense debate in New Zealand.

This doctrine provided the rationale for British claims to sovereignty over Aotearoa, particularly in the South Island, which Lieutenant William Hobson declared \"terra nullius\" in 1840.

While the New Zealand government maintains that the doctrine is not relevant to the country, citing the Treaty of Waitangi as the primary framework for Māori-Crown relations, critics argue that its impact is still evident in the state\'s structure and assumption of governance rights.

The debate has gained momentum following the Vatican\'s formal repudiation of the doctrine in 2023. This has led to calls for the New Zealand government to officially reject the doctrine and address its lasting effects, including Māori land dispossession and persistent inequalities.

However, some scholars argue that Britain\'s colonization of New Zealand was not directly influenced by the Doctrine of Discovery, citing the country\'s separation from the Catholic Church and its focus on trade rather than territorial expansion.

As discussions continue, many Indigenous advocates stress the importance of rediscovering traditional ways of self-governance and care as a means of rejecting the doctrine\'s legacy.

Global Repercussions of the Doctrine

The Doctrine of Discovery has had far-reaching global repercussions, shaping international law and the treatment of Indigenous peoples worldwide.

This 15th-century principle, originally used to justify European colonization, continues to impact Indigenous communities today:

● It has been used to legitimize the colonization of lands outside Europe, disregarding existing inhabitants.

● The doctrine has influenced legal systems globally, including in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

● It has led to the seizure of Indigenous lands, displacement of peoples, and the erosion of Indigenous rights.

● The United Nations has recognized it as the \"shameful\" root of discrimination and marginalization faced by Indigenous peoples.

Despite growing criticism and calls for its repudiation, the doctrine\'s legacy persists in many countries\' legal frameworks and policies, continuing to limit Indigenous peoples\' human, sovereign, commercial, and property rights.

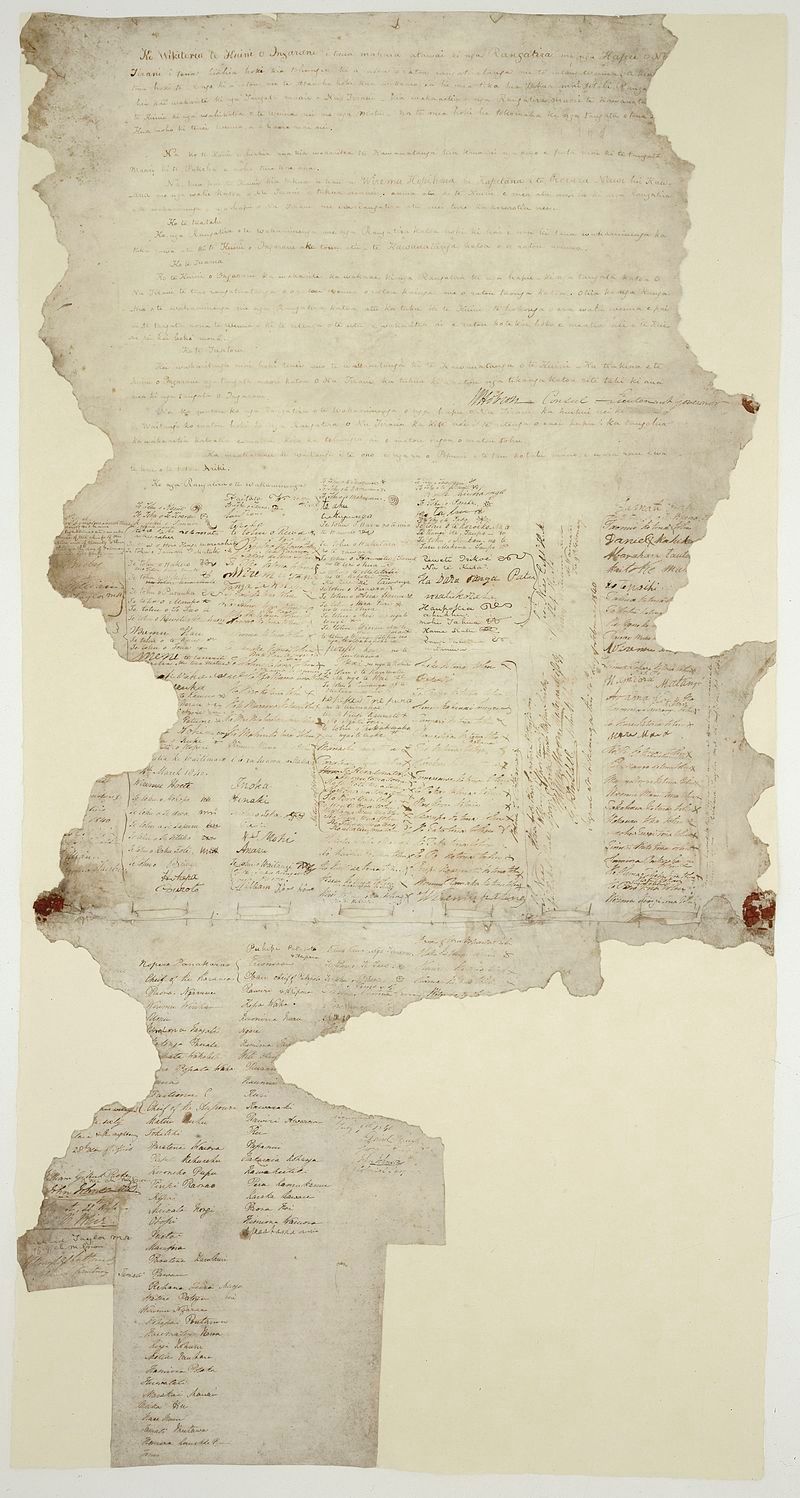

Te Reo Text vs. English Version

The Treaty of Waitangi exists in two versions: Te Reo Māori and English, with significant differences in meaning and interpretation between them.

The Māori version, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, was signed by most Rangatira and is considered the founding document of New Zealand.

Key differences include:

● Sovereignty: The English version cedes \"all rights and powers of sovereignty\" to the British Crown, while the Māori version grants \"kawanatanga\" (governorship).

● Land rights: The English text guarantees \"undisturbed possession\" of properties, while the Māori version promises \"Tino Rangatiratanga\" (full authority) over \"taonga\" (treasures).

● Governance: Many Māori believed they were granting authority over British settlers only, retaining the right to manage their own affairs.

These discrepancies have led to ongoing debates about the Treaty\'s interpretation and implementation, shaping New Zealand\'s social and political landscape. The oral discussions preceding the signings may have been as crucial as the written texts in shaping Māori understanding of the agreement.

Legal Implications of Text Variations

The differences between the English and te reo Māori texts of the Treaty of Waitangi have significant legal implications, particularly in how the Treaty is interpreted and applied. These variations have led to debates about sovereignty, land rights, and the extent of Māori authority.

The Māori version, signed by most rangatira, emphasizes \"tino rangatiratanga\" (absolute authority) over their lands and taonga, while the English version frames this as a cession of sovereignty to the Crown, creating a fundamental conflict in interpretation.

To address these discrepancies, New Zealand courts and legislation often rely on the \"principles of the Treaty\" rather than its exact wording. These principles aim to reconcile the texts by emphasizing partnership, active protection of Māori rights, and redress for breaches.

For example, the Waitangi Tribunal, established under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, has exclusive authority to determine the meaning and implications of both texts.

This approach allows for flexibility in applying the Treaty to contemporary issues but has also been criticized for diluting Māori sovereignty as guaranteed in te reo Māori text.

Māori Sovereignty and Rangatira Perspectives

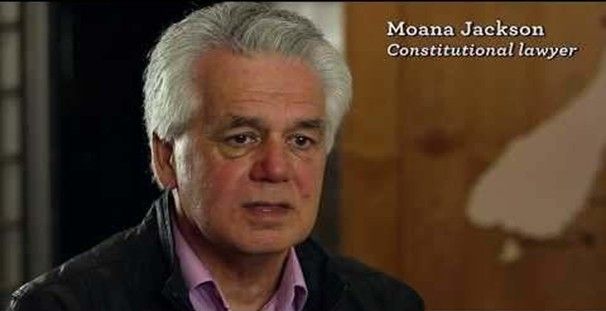

Māori sovereignty, or tino rangatiratanga, is a complex concept that goes beyond simple self-determination. According to Moana Jackson, tino rangatiratanga is more akin to sovereignty and exists independently of state sovereignty.

This perspective is supported by the Waitangi Tribunal\'s finding that Māori who signed Te Tiriti did not cede sovereignty to the Crown. Instead, rangatira agreed to a relationship of shared power and authority with the Governor, retaining their authority over hapū and territories while granting the Governor control over Pākehā.

The concept of rangatiratanga has evolved over time, with Māori leaders adapting to new political structures to assert their priorities. For instance, Ngati Porou rangatira became members of the Legislative Council and used roles as Assessors to reinforce their own positions.

Today, Māori leaders continue to seek a relationship with government authorities based on real cooperation, mutual support, and reciprocity, rather than token consultation.

This ongoing pursuit of tino rangatiratanga challenges the public sector to develop new partnership arrangements with Māori, recognizing their right to autonomy and self-government at local, regional, and national levels.

Impact on Indigenous Land Rights

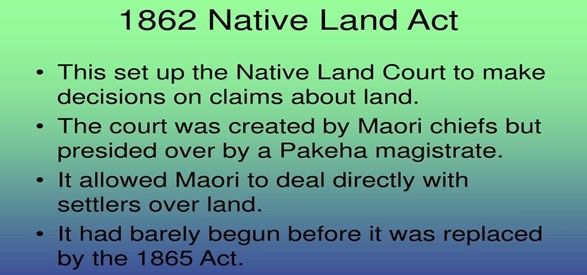

The Treaty of Waitangi and subsequent legislation had profound impacts on Māori land rights in New Zealand. The Native Lands Act of 1862 established the Native Land Court, which converted customary Māori land titles to Crown-granted freehold titles, making it easier for settlers to acquire land directly from Māori owners.

This process, along with confiscations under the New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863, led to massive land loss for Māori.

● By 1865, the Crown had acquired two-thirds of New Zealand\'s land area from Māori, including most of the South Island.

● The 1863 New Zealand Settlements Act allowed confiscation of 1.3 million hectares from iwi deemed to be \"in rebellion\".

● Legislation like the 1967 Māori Affairs Amendment Act further eroded Māori land ownership by enabling compulsory conversion of Māori freehold land to general land.

These policies, rooted in the Doctrine of Discovery, systematically dispossessed Māori of their ancestral lands and continue to impact indigenous rights today. Recent efforts, including the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975, aim to address historical injustices and restore some measure of Māori control over their traditional territories.